As a folk witch, I spend a lot of time thinking about previous ages and the beliefs shared by those people. But I also live in modern times; I’m alive here and now, not somewhere else. Sometimes, the ideas and cosmologies inherent in the old lore feel almost incompatible with who we are as modern humans living on the edge of capitalism’s collapse. But it simply isn’t so. In fact, it’s possible that this age needs animist spirituality more than ever.

I’m not interested in putting forth a rigid definition of animist spiritual practice. I’m not interested in deciding who can or cannot call themselves an animist. For one thing, it’s just a boring question. It also assumes a singular definition of lived animism rather than a plurality of practices. I’m more interested in the diversity that already exists among different expressions of animism, even if this challenges the concept of animism itself as a cohesive paradigm. Concepts and ideas aren’t that important, after all. Animism is simply the best term we have for these practices, but we must accept in advance that the term itself is flawed, imperfect from its very beginnings.

Let’s just say it, then: originally, animism was a word made up by white people (specifically, 1800s scholar Edward Tylor) to describe indigenous spiritualities that often (but not always) predate the worship of deities. It is usually applied to the belief in non-human spirits, to the belief in a complex spiritual world governing the forces of nature, entities dwelling within trees, hills, storms, creeks. The idea of spirits at work within flora, fauna, and land features is indeed ancient, and we now know that these beliefs are not a novelty among Siberian shamans, but were once widely held among ancient peoples of virtually every known culture. Today, animism is a term used in modern anthropology to describe a vast and diverse group of spiritual practices thought to be older than organized religion. The interesting pivot here comes from within witchcraft scholarship, specifically in the works of Emma Wilby, Carlo Ginzburg, and their contemporaries, for as this group began to unpack the history of witch lore and folk-magical practice in western Europe, they discovered that old forms of European folk magic actually preserved animist elements that were similar to the practices of shamans and seers in other parts of the world. The term animist, which originally smacked of ethnocentrism, was found to apply equally to the spiritual roots of colonizing cultures, and the fear and hatred of those roots gave rise, in part, to the fear of witches.

In reality, there has always been a disconnection between academic discourse on animism and the lived realities of people who fit within this umbrella. This concept was, after all, defined and pioneered by people who looked down on those who held such beliefs. Modern animism might, in fact, be the first instance of people actively self-identifying with the term. For those of us who chose to identify this way in modern times, it can mean many things. Many of us observe ancestral folk-magical traditions that involve spirit interaction and otherworldly travel. Many of us identify as witches, warlocks, herb doctors, cunning folk, or sorcerers. For myself, I look to the charming traditions of my Scottish and Appalachian ancestors, which preserve the means of calling to plant spirits, warding baneful entities, and entreating fortune and favor from the invisible world of spirits, including the dead.

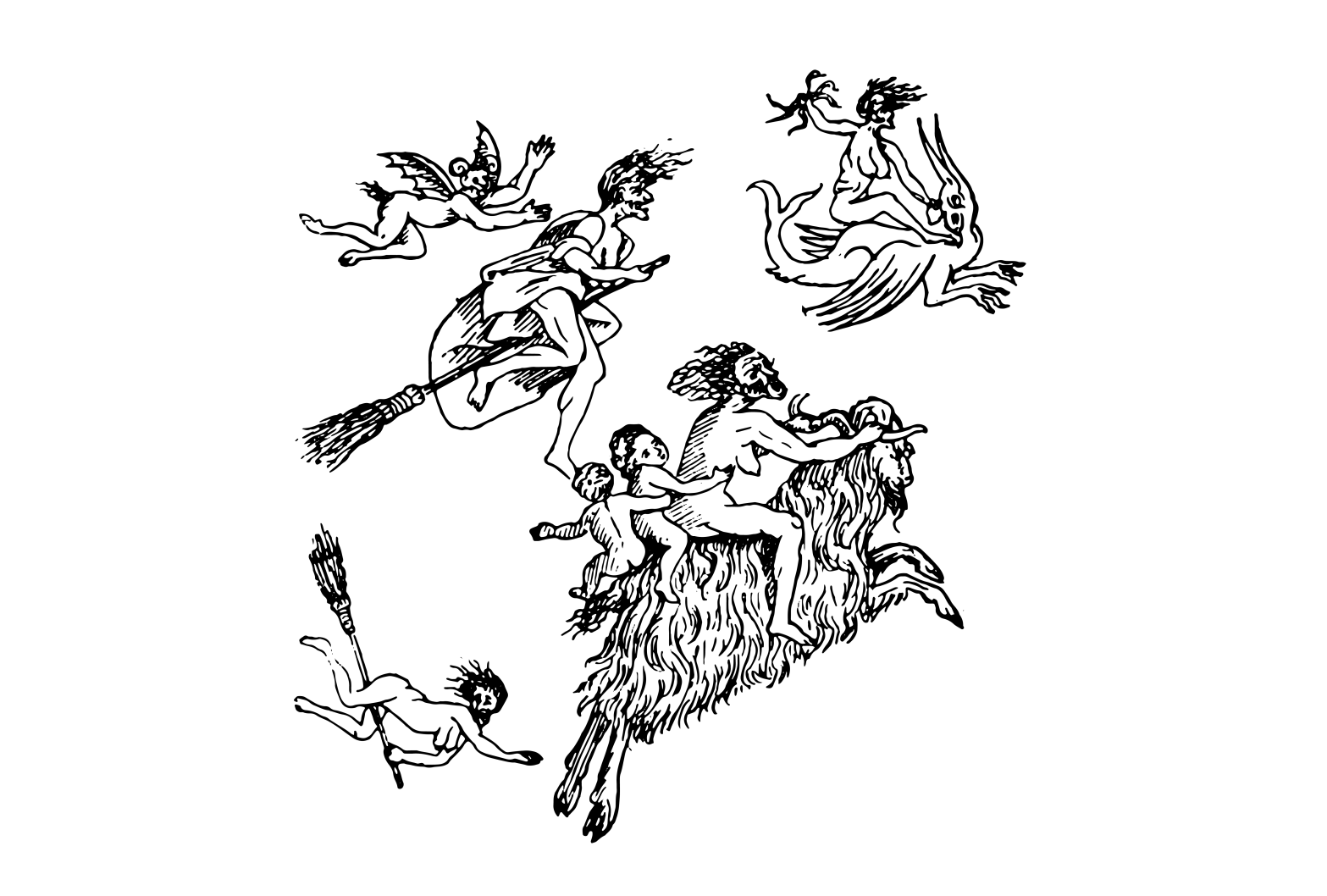

One of the things I tried to accomplish in A Broom at Midnight was to shine light on the connection between animist views of the otherworld and the flight to the witches’ sabbat, for these otherworldly journeys are iterations of the same spiritual phenomena, as vibrant today as they were hundreds of years ago. Like the shaman’s journey, the witch’s departure into the world of spirits is not ornate, but simple; not elaborately choreographed, but improvisational; not imaginary or merely “visualized,” but vividly psychonautic and ecstatic. When we, as witches, contextualize this ecstatic praxis as a part of the greater tapestry of animist spirituality among human beings everywhere, we are better able to understand ourselves, but we are also actively dissolving the racist framework that would cast some spiritualities as “civilized” and others as “primitive.” We witness for ourselves that animist spirituality is every bit as complex, sophisticated, and ornate as theological traditions. We also begin to recognize that animism does not exist in a vacuum, but blends and syncretizes with other forms of faith. Even Frazer in The Golden Bough recognized that many cultures experienced animism and theism at the same time (though he mistakenly viewed theism as a more “evolved” spirituality).

Often, the choice to identify as a modern animist is simply an acknowledgement that our spirituality is informed by these types of beliefs, even in broad strokes, that regular interaction with spirits is a part of who we already are, inseparable from the spiritual cultures in which we are rooted. I like this meaning best, for it is the roomiest and probably applies to most practitioners under this umbrella. Perhaps we only interact with a handful of specific spirits in our regular practice. Perhaps we live in an urban area and keep potted plants rather than strolling a deep forest. Perhaps our physical condition prevents us from taking long, wandering hikes to connect with land spirits. These activities are merely examples of practice, not edicts to be followed. In whatever ways we are able, in whatever way we can, what seems to unite most modern animist practice is the recognition of selfhood in the non-human other; the belief that a forest, a lake, a tree, or a frog is possessed of a spirit and a selfhood that exists for its own purposes and operates based on its own rules. We share a world with these beings, but they can never belong to us. They are not ours. On the contrary, if we act without cunning, we are often at their mercy, not the other way around.

This approach to modern magical practice comes with certain concrete benefits. When forging a relationship with a spirit governing a particular plant, we will usually spend a great deal of time observing it, watching how it grows and withers, how it reacts to its environment. We realize how unique each species is, and in this realization, we arrive at our own doctrine of signatures. Suddenly, the old “correspondences,” though certainly viable in a broad sense, become less useful to us personally. We can discern for ourselves the ways in which a particular plant is martial, venereal, or saturnine. We’ve simply no need for a book to tell us how to read a plant or an animal anymore. We have eyes. Similarly, we are less bound by ceremonial traditions of spirit evocation because we learn to interact with spirits using simpler, more direct methods, forging personal relationships with very real benefits in the form of revealed charms, sigils, and lessons that guide us in the progress of our craft. These practices do not preclude us from participating in modernity, but they provide a grounding center, a moment of solace that restores and realigns us. We are reminded that human beings are not the center of the world or the pinnacle of evolution, but are just another form of living thing, no greater and no less.

The extension of this same grace to what we might call “dark” spirits is perhaps less commonly held among modern animists, though I believe this is changing. The church’s vast colonizing influence in Celtic countries transformed the belief in ancestor spirits, recasting the honored dead as elves, fairies, and demons. These beliefs were carried over by immigrants to the new world, and even today, I regularly come across witches who perform routine exorcisms and cleansings to threaten, berate, and harm dark spirits without even trying to understand them first. Though malevolent spirits are real, they are rarer than one might think simply because humans aren’t all that interesting. We are more alike than we are unique, and though it is human nature to imagine ourselves special and intriguing to the spirit world, this is a narcissistic overestimation of our importance. The unpretty truth is that we are usually regarded by spirits (if they regard us at all) as mere pests or trespassers.

If we acknowledge that the spirit world is as diverse and interwoven as the ecological world, we must also be ready to admit our limited perspective within it. In the absence of our demons and our angels, we witness the difficult, more complicated truth: a spirit world of natural predation, of usually faultless harm, of carnivorous, parasitic, or toxic entities that may often be unaware of their influence or even of our existence. We begin to understand that we, as human beings, are not actually very important. Usually, we’re just in the way, much like standing in the path of a flood or walking too close to a hive of bees. A modern animist’s approach to warding is usually not to destroy, but to understand. Our ghosts and phantoms, our hauntings and demons and shadows are not enemies, but kin, and it is wiser to establish clear boundaries and agreements than it is to declare war on a kingdom that outnumbers us.

The most difficult question, and the one I do not have the ability or the desire to answer here, is how the animist negotiates the relationship with modernity, with capitalism, with personal responsibility in the face of ecological collapse. Ideally, we take ownership of the choices we have and try to respect the other beings in our world as best we can. But for the past fifty years, corporations responsible for 99% of environmental damage have been waging expensive disinformation campaigns in order to convince us that it is the “masses” who are responsible for climate change. Billionaires squeeze profits from the working class like a spider sucks its prey. Poor and disempowered individuals are blamed for all manner of disasters. But who has built the web? Much of our disconnection to the world of flora and fauna is not a conscious choice, but a choice made for us by corporate powers and the governments that bow to their interests.

On the other hand, the romanticization of the country life, so ubiquitous in aesthetics like “cottage-core” and “witch-core,” portrays only the consumption and taming of nature, not the realities of planting and harvesting, not the sweat, the ugliness, the bug bites, the scratches and sprains that come with actually living alongside nature. But who am I to judge? Perhaps even this representation is an awkward step forward. I believe that the massive political shift we need in order to prioritize the other beings in this world will come not through preaching or scolding, but through the act of personal witness, through individuals coming to love and appreciate the wild around them, and the more we can do to facilitate this change, the better.