One of the questions I receive frequently is why I and others choose to identify the craft we love and practice as folk witchcraft rather than either Wicca or traditional witchcraft. The intention behind the question is almost always innocent, and the short answer is this: folk witches do not do or believe all of the things Wiccans do, and though folk craft is often discussed as a branch of “traditional” craft, it does not necessarily adopt the modern frameworks or ritual approaches designed by Robert Cochrane, Cora and Victor Anderson, or Andrew Chumbley, who represent the three most popular branches of traditional craft today. Unfortunately, sometimes the popularity of a given tradition results in a kind of enforced assimilation of magics, irrespective of the local or ancestral folk traditions of the practitioner (i.e., “If you don’t celebrate Ostara, you aren’t engaging with the whole Wheel of the Year,” or “If you’re not laying a compass or treading the mill, you aren’t practicing ‘old craft.'”). This erasure of diversity in older forms of craft is problematic for many reasons, not the least of which being its utter disregard for historical accuracy.

And yet, this question of where folk craft “fits” is more complex than it first appears. Folk witches do have more in common with Wiccans and traditional witches than not because the rituals we inherit and devise are often drawn from the same sources of wisdom that influenced Gardner, Cochrane, and others. Though I usually prefer to think of myself simply as another witch and leave the discussion of movements and categories to others, this question of distinction, if approached respectfully, can be a rich one that challenges us to recognize the many unique currents operating under the umbrella of modern witchcraft as a whole. By positioning ourselves within the broad and diverse landscape of witchcraft movements, we can better understand our differences, not as schisms or conflicts of ideology, but as a diversity of thought and approach that should be celebrated within the larger discourse of modern craft. All of these traditions are beautiful and unique, and recognizing our differences need not be governed by the same old boring and elitist question of who is more “authentic.”

In terms of ritual construction, folk craft is diverse and flexible. Traditional witches working in the Cochrane current perform the laying of the compass, the houzle or red meal, and the treading of the mill, all rituals designed in the mid-twentieth century by Robert Cochrane in his Clan of Tubal Cain. Andrew Chumbley’s tradition of what is now called sabbatic witchcraft, another branch of traditional witchcraft, is beautiful in intellectual and ritual approach, drawing on witch-lore and historic charms, but is also quite academic in nature, building upon Chumbley’s work in oneiric occultism as outlined in his books and essays. Folk witches may share some practices with these traditions, but ultimately, we prefer to draw our rituals and practices more directly from folk charms, grimoiric texts, and local and ancestral lore (often meaning one’s spiritual ancestors, not necessarily genetic ones, mind you; defining one’s “belonging” to a culture along purely genetic lines is the stuff of racism). Our construction of sacred space may adapt magic circles from old grimoires or simple “saining” traditions in folk magic. Offerings similar to the red meal are frequent, but these approaches are drawn directly from lore-born and ancestral folk customs for propitiating spirits: the offering of smoke, of cider or wassail, of milk and bread left out for the faeries, and of adaptations of eucharistic rites that echo folk-religious fusions.

On the question of cosmology and ethics, folk craft offers no unified answers. While Wicca offers a version of reincarnation, a summerland, and a three-fold law of return, folk craft is too diverse in its spiritual cosmologies to reduce to one definition. The cultures of our ancestors, along with our own experiences and explorations, determine how we view the world and the rules of operating within it. Most frequently, there is a recognition of the “other world” into which the witch may cross to interact with spirits and ancestors, but this world is wild and dark and usually defies efforts to map its geography or rules in human terms. Individual folk witches operate based on relationships with spirits, particularly familiar spirits, establishing boundaries and rules of personal operation based on experience during these sojourns. Folk craft is decidedly animist in its recognition of animal, plant, and local spirits as important partners. Baneful magic is perfectly valid, but is usually regarded with care for its impact.

In the Feri tradition founded by Cora and Victor Anderson, there are a multitude of defined witch-gods with which the practitioner may commune and consult. In folk craft grounded in the lore of Western Europe and North America, there is usually a recognition of the Devil as a teacher and guide based on his prominence in old witch lore. Also present is a female figure who may be Brigid or Mary, depending on the witch. The Faery Queen and King, who so frequently arise in Celtic lore, may also be invoked to attend rites. These figures coalesce into a syncretic dark king and queen in my own practice, but for other folk witches, these figures may be distinct in the manner of polytheism or may be less important. A folk witch with Slavic ancestry, for instance, may feel more comfortable calling upon Baba Yaga, and this is well and good, for those ties will strengthen that connection and ground the witch’s practice in something old and personal.

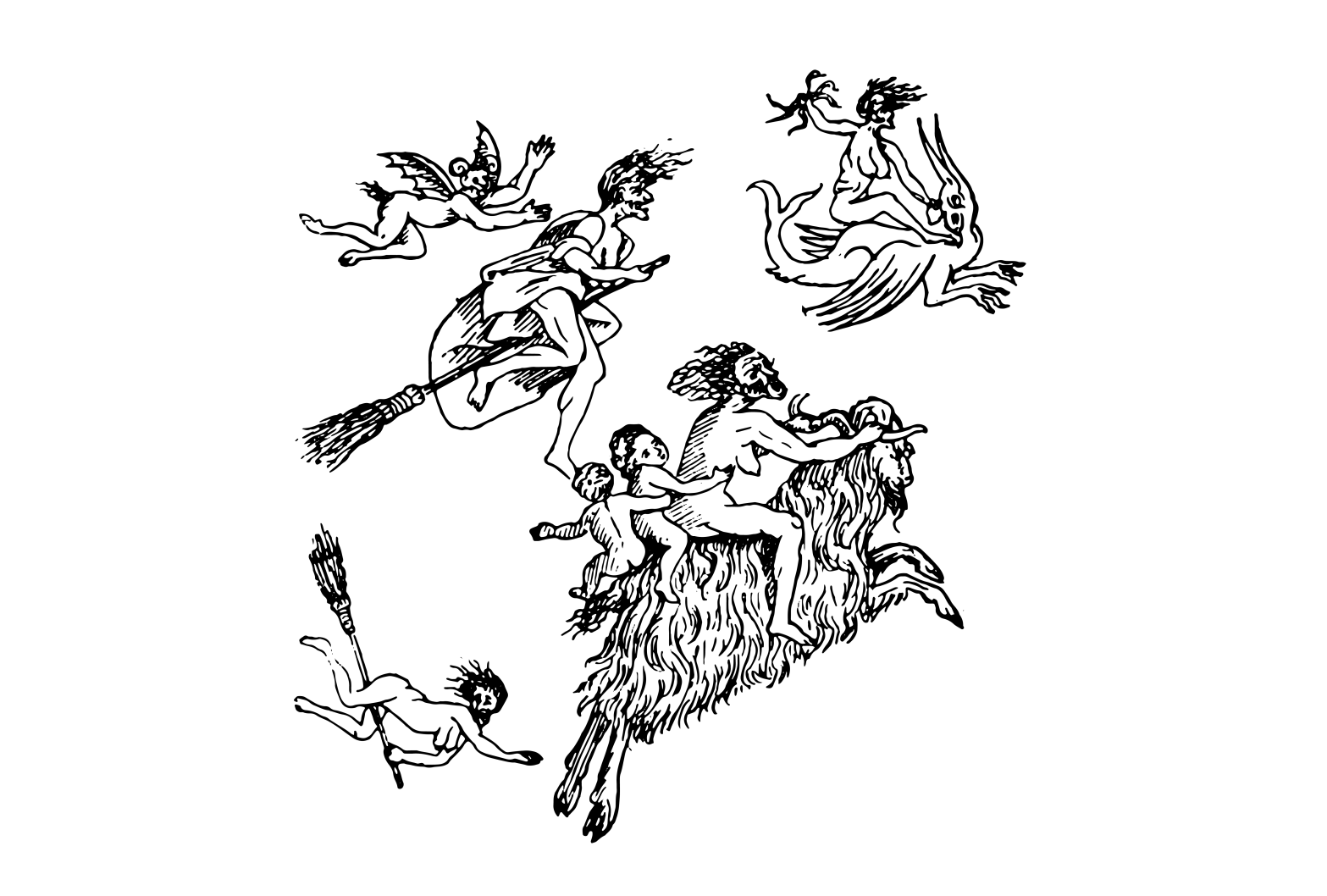

Although the terms “folkloric craft” and “folk magic” have become popular in recent years to describe branches of craft that draw heavily and directly from lore, they carry different connotations that are worth exploring. On the one hand, we have folk magic, which describes the actual, historic charms and superstitions worked by practitioners who may or may not identify as witches. On the other, we have folkloric craft, which devises rituals based on stories about witches in myth and lore, often more ornate than simple folk charms, and usually more focused on recreating visionary experiences based on mythic narratives. Folk craft encompasses both of these things. By blending historic folk charms that were practiced by ancestors with inspired wisdom from witch narratives in folklore, practitioners balance witchcraft as a practice and a personal spirituality, keeping what is good and old while breathing life into the ancient tales that continue to teach us today.

Perhaps most distinctly, folk witches, unlike practitioners continuing in the traditions of Gardner, Cochrane, Chumbley, or the Andersons, usually prefer to practice our craft alone or in very small groups instead of in a modern coven. Part of this is practical, since it allows us to focus more on our individual ancestries, locales, and spirit-led traditions, but part of it is also historical. Hundreds of years ago, folk craft practitioners worked alone or perhaps with one or two others. This is as true in the case of the cunning folk and fairy doctors as it is in the case of pow-wows, herb doctors, pellars, and other charmers. There was no fixed curriculum of magical instruction for these sorcerers of old, but they were aware of ancestral and local charms and customs and, if they were lucky, owned at least one grimoire, such as the Grimorium Verum, The Magus, The Sixth and Seventh Books of Solomon, or The Grand Grimoire, drawing from the sigils and incantations therein to enrich their art. Through experimentation, they developed their own styles and approaches to craft. Their solitary practice was not a weakness, but a strength, allowing them to focus on a particular area of the charming arts, mastering it to the level of infamy, such as highland seers who focused on finding lost people and objects or Cornish pellars who tended to healing and warding. Rather than empowering practitioners to root more deeply into their own cultures and folk traditions, most magical orders and schools from the late 1800s on have functioned as places to forget these treasures, to become assimilated into a one-size-fits-all curriculum that rewards conformity over diversity, paradigms over cultural flavors and their variations. Perhaps this is part of why our kin operating in the rich and potent currents of brujeria, stregoneria, and rootwork avoid these spaces. For folk witches, a more rigorous curriculum is to be found in studying the old folklore, superstitions, and herbal wisdom, in perusing treasures at a local flea market, in getting to know the wild herbs that grow on our own land, and in self-reflexive contemplation on where we come from, how we got here, and what our traditions mean. While “folk” has in the past held the connotation of “poor,” it would be a mistake to imagine that these treasures leave us wanting, for they are deeply nourishing.

And yet, despite all of these differences, folk witches have strong ties to practitioners of Wicca and to practitioners within sister veins of traditional craft. The lore preserved in Aradia, which became so foundational to Gardner’s vision of Wicca, is also important to many folk witches (though we might also read some of Leland’s other folkloric volumes, which are equally stunning). The use of the forked staff or stang, popularized by Cochrane, is prized by folk witches for its presence in The Grand Grimoire as a “blasting rod” and in the lore of the distaff and forked branch in superstition. The sigil techniques recommended by Chumbley are also employed by folk witches to decipher the names and natures of familiar spirits and to empower all manner of charm, modeled after the many seals and sigils recorded in the grimoiric traditions beloved by both movements. In truth, our traditions, distinct as they may be, are nourished by the same sources of lore and spiritual revelation, and for these reasons and many others, we witches of our various tribes are and always will be kin.