It should come as no surprise to pagans anywhere today that I insist on the dark tide of winter as a season relevant to many old forms of folk witchery. Whether we call it Yule or Winter Solstice or by any other name, the magic of this season enfolds so many old superstitions, folktales, and charms. But many of the old treasures of folk witchery do not use the word Yule; it is in the folklore of Christmas that we most often find these historic accounts of divination, spells, and spirits.

Most of our ancestors who practiced folk craft observed the rites of Christmas, and despite what many would have us believe, they most likely understood, in their own way, that their favorite Christmas traditions were pagan in origin. Our great-great-grand-somethings were no fools. They knew that the symbols at the heart of Christmas, gathered like jewels in a chest over hundreds of years, were older than the church and its story of the Christ child. They understood that belief and magic are complex and paradoxical at times; that to observe Christmas and to practice our art was not incongruous, but as natural as the complex evolution of the holiday itself over the ages. I’m not advocating for all pagans to embrace Christmas. (I am not even a Christian, so that would be ridiculous.) But for those who are truly interested in forms of real folk witchery alive and active in the early modern period, I am suggesting that we perhaps look beneath the surface of things, lest these treasures melt away from our grasp like snow.

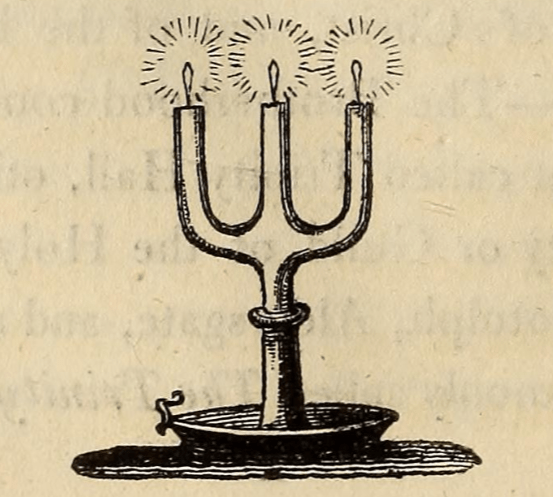

One older practice associated with Christmas that is less prevalent today involves the use of a three-tapered candle resembling a fork. William Hone, in 1823, calls it a “triangular candle,” and provides the following illustration of its form:

Hone attests to the use of this candle as a part of Easter celebrations, but Thomas Hervey, in 1837, describes its use among the Irish peasantry, insisting that they were lit as “Christmas candles,” with garlands of evergreen strung around them as a kind of replacement for or extension of the Yule log. Their lighting was observed with serious ceremony, and once the three prongs had burned down into one, the remaining single-wicked candle was saved for use later in divination by gazing into its flame.

Even today, the Christmas candles adorned with evergreen garland, which are often lit in sequence relating in some form or another to the nativity story, are actually a modern iteration of the Yule log. Whereas poor and rural families gathered about the log burning in the fireplace, wealthier households began lighting candles decorated with garland as a kind of posh replacement, and it is this tradition that gave way to the decorated candles so many place as the centerpiece of the Christmas feasting table, with or without knowing that this is, in fact, the Yule log around which they gather.

Some of the old witching traditions of Christmas call on ancient spirits in the form of saints and legendary pseudo-biblical figures, not the least of which being the three Magi, whose names are Balthazar, Melchior, and Caspar. The consecration of Three Kings Water on the Twelfth Night is a well-known tradition of Scottish origin, this water being used to bless doorways and persons for protection throughout the year. In a broader sense, though, there is something exquisite in the survival of these three sorcerers of the ancient world in Christmas traditions, allowing us as charmers, conjurors, and cunning folk an entry point into a celebration that can feel, on the surface, very Christian. The rituals and lore of the three Magi are emblematic of the path of sorcerous folk through this holiday long before us, like a sign left along a winding trail, a clue hinting that even serpents may celebrate the luminous star that shines on this night–if perhaps in our own shadowed ways.

This is not to mention the mountains of specific charms performed, traditionally, on Christmas eve or Christmas day. Scot (1584) describes a talisman called an Agnus Dei or lamb cake, which is made from wax, balm, and holy water. The talisman is said to protect against all manner of woes, both natural and unnatural, and to ensure blessings when carried on the person. Inside of the wax is placed a small roll of parchment containing the following written charm:

Balsamus & munda cera, cum chrismatis unda

Conficiunt agnum, quod munus do tibi magnum,

Fonte velut natum, per mystica sanctificatum:

Fulgura desursum depellit, & omne malignum,

Peccatum frangit, ut Christi sanguis, & angit,

Prægnans servatur, simul & partus liberatur,

Dona refert dignis, virtutem destruit ignis,

Portatus mundè de fluctibus eripit undæ.

Likewise, the “waist-coat of proof” charm was said to have been worked on the evening following Christmas Day. It functioned as a wearable talisman, embroidered on an item of clothing, which would render one protected from bodily harm. The embroidered image is interesting for its resemblance to many two-headed figures, including Janus. One head wears a hat and a beard, and the other a crown, but with a beastly, frightening face. The charm, it is said, must be embroidered onto the cloth “in the name of the Devil,” which is a common phrasing in Scottish witch-lore.

But none of these sorceries, even the decidedly heretical ones or the clearly pagan ones having nothing to do with Christ, are available to us if we eschew everything labeled “Christmas” instead of “Yule.” We cast them away, despite hundreds, perhaps even thousands of years of magical tradition at our fingertips. Some of the old witching traditions of Christmas are almost completely forgotten, replaced by “Yule sabbat ritual kits” that can be purchased on the internet and paint-by-numbers-style witchery guides with no thought to the cultural origins of our magics and the generations who preserved them for our use. And so, I believe it is worth exploring where the modern pagan dislike for the word “Christmas” comes from, if only to understand how we arrived at this place.

The most obvious culprit, in my opinion, is the hateful and abusive form Christianity often takes today. How dare we take “Christ out of Christmas,” they cry out, and yet, without Christ, there is still a tree, still an ancient, sorcerous spirit who descends down the chimney, still mistletoe and holly, still lights, logs, and candles, still songs and drink, still gifts and mirth; there remains, in the complete absence of Christ, everything that made Christmas what it was to begin with, for the season we know was, in fact, already old when Christianity was young. For those who have suffered trauma in their youth at the hands of Christianity, it is perfectly understandable to want nothing to do with the thing.

Unfortunately, the pagan distaste for Christmas also comes, in part, from disinformation, especially from the common claim among modern witchcraft traditions that true witches do not and cannot celebrate Christmas. This is not only untrue, but harmful to the preservation of our traditions, for the modern forms of pop-witchery and insta-craft will always lack (in my opinion) the elegant simplicity of the old charms and rituals of the season, even if those treasures are described in our lore as “Christmas superstitions” and not explicitly as “Yule rites” (even if that is what they truly are beneath appearances). In order to recognize these treasures of craft for what they are, we must see the word “Christmas” through the long, wide scope of history–not as a single story, but as a cacophony of echoes having more to do with tradition than belief. In short, it actually matters very little to the folk witch whether there is “Christ in Christmas” or not, for the living heart of the season is the same.

And the heart of the season is not only one of light, but one of darkness as well. It was Charles Dickens who referred to Christmas eve as the “witching time for story telling.” Tales of spirits, ghosts, and other creatures who thrive in the dark time of the year were commonly shared around the fire on this night for hundreds of years. Puritans in the new world attempted to stamp out the custom, for it smacked of the old superstitions. They failed, however, as evidenced not only by Dickens’ ever-popular A Christmas Carol, but also by the works of Washington Irving and many folklorists who preserved the old darkened tales. The resurgence of Krampus traditions is perhaps one of the most prevalent examples of an old, lore-preserved spirit associated with Christmas, but there is also La Befana, who is said to be an old woman who offered the three Magi directions as they searched for the Christ child, and who has now become a kind of sorcerous Christmas spirit who very obviously resembles the early modern image of the witch. Frau Perchta plays this role as well, though in a more terrifying capacity, for the long knife she carries is used to punish naughty children by gutting them.

But the most obvious example of a thriving Yuletide spirit is Santa Claus / Father Christmas / Saint Nicholas himself, who is, of course, the very image of a sorcerer, embarking upon his flight across the night sky, transvected with the aid of his trusted magical steeds, entering houses through chimneys and key-holes, laying his gifts beneath the shrine of the illuminated evergreen tree. And it is beneath this altar that we leave our spirit offering to nourish him, consisting perhaps of milk and cookies or various other things, depending on tradition. This tree is a symbol of endurance through the bitter cold, a totem to bring joyfulness in the dark, a fetish to conjure what is outside us within us, to embody the ever-vital qualities of those green winter forests. It is the shrine around which so many still gather, even if they no longer recognize the language it speaks. Somehow, we still feel its potency without even trying, perhaps by instinct or some ancestral twinge of magic that stirs within us, whether we will it or no.